Chapter 13 Our Farming Practices

I think we have things so easy climatewise that we do not do everything possible to get the maximum production. I know that generally all Australian farmers are very efficient, but we are not all so methodical as Americans, for instance.

In America, before they plant a paddock of turnip seed, or rape or anything like that, they test the seed thoroughly first. And in Sacramento Valley, because they test their seed and inoculate it against all sorts of things, there is not a square metre of their paddocks that is not perfect.

Many Australian farmers, because they have things relatively easy, do not test their seeds before sowing. We buy seed that is stated to have been germination tested, but we often do a home trial in case the seed had been kept too long and will not germinate as stated.

This home test takes only a few minutes to prepare, and I consider it would pay all Australian farmers to do this. Just put some cotton wool on a saucer and soak it in water; then put 50 to. 100 seeds on it and check the percentage that germinate. This costs nothing, but is very effective. In 1989 we tested some turnip seed by this method and knew that we had good seeds when we sowed another 420 acres (170 hectares) ten days later. It is futile blaming the seed company if there is poor germination.

We cannot afford today to leave anything to chance. Farming is a very complex business, and we must not approach our task in a happy-go-lucky way. If rape seed does not come up because the seed was no good, or clover does not produce nodules because we forgot to inoculate the seed with inoculum before we planted it, excuses are unacceptable. If a job is worth doing it is worth doing properly.

This applies particularly to the farming world, because anyone can see if you have been careless and have not got an even strike in your crop So, on our property, we try to take notes of the seasons and rainfall and various things that should be attended to at different times of the year. We continually check to make sure we are doing the right thing and are not missing anything. It is so simple to miss out on something.

In 1974 the cattle market crashed. Cattle prices dropped by half and many Australian cattle producers went bankrupt or left their properties. During 1974, 1975 and 1976 the prices received were well below the cost of production and many graziers and cattle fatteners would not sell cattle bought just before the 1974 crash until they could get their money back, plus something extra towards running expenses. They thought this was their only hope of survival.

We were caught the same as everyone else, but we decided to sell beef at half the previous sale prices and replace with stores at half previous purchase prices.

In the 1973-74 season we bought stores at $87 average price per head and sold beef at an average net price per head on the property for $207.90.

By trading and buying cheap stores we were able to offset the cheap purchases of store cattle against the cheap sales of beef cattle, whereas the graziers who held on to their cattle until they could get a reasonable profit on their previously-bought steers had no cheap ones to help balance their trading activities during the financial year of 1974-75.

During these three dreadful depressed years we bought 3600 steers for an average price delivered of $38.46 per head and sold bigger numbers of fat cattle, because of our own breeding programme, for an average net price of $126 per head. This showed a net gross gain of $87.54 per head per year on purchased cattle.

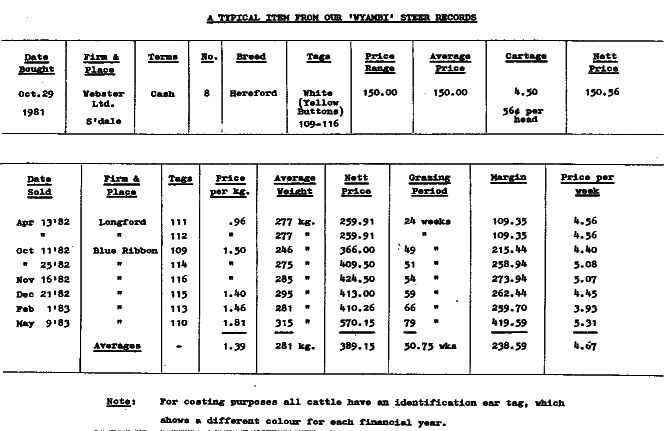

While this was an extremely low margin, it was sufficient to about break even and not show a loss. Our total cost to run a beast at this time was about $1.50 per week, or $78 per year. To this had to be added interest at 10 per cent on cattle purchases, which was $4, or a total cost of $82 against a return of $87.54. We only really survived by our meticulous office records available on stock purchases and sales. The attached sheet of the early 1980's shows that we could glance at our books and see how we were performing at the time and how the figures compared with past years.

Costing

Our 1973-74 experience showed the need to keep on trading, although it is a more difficult position if you are fully a breeder. We were breeding and buying in also, and this made the enterprise viable, but only just, during this emergency. It was the worst cattle crash during my 50-odd years of grazing, and it took many people out of the beef industry for all time.

It was a very difficult period. A few times when I jumped out of the car, after driving to Wyambi I fell over. John said, 'Take it easy Dad. You can only do so much.'

If I am tense with business activities I have a good hot bath for perhaps an hour and then I am re1axed and can generally go to sleep without any trouble. It is not the big items that get any one run down; it's the little nagging problems. I also love to read wild west books, not silly ones, but any of Louis L'Amour's are always good reading, educational and relaxing.

East Wyambi - sorting cattle.

Section of l,500 head of cattle being moved at Wyambi.

Depicting cattle of various breeds. All dehorned.

Tagged with different coloured ear tags so that date

of purchase and other details can be recorded.

I remember advising my son about sound business practice when he was a little boy. He wanted to buy a lawn mower and said he could easily pay for it. I asked him whether it would be a payable proposition, because we had another chap mowing the grass for a certain figure.

My son said, 'I can do it for that figure.' But I pointed out to him that he had to include the cost of his lawn mower and depreciate it.

'I don't have to do that,' he insisted. 'I sold a fat steer, so I'll pay for my lawn mower out of that.'

'Yes,' I replied, 'you can do that, but each business has to be separate. The lawn-mowing business has to pay for itself. It is no good taking a section of your business and having it prop up another section, so you must book down the cost of the lawn mower and how much you earn with mowing so you can pay your lawn mower off.' He agreed that it was a good idea, and that is what he did; he costed each project separately.

Although the projects we have undertaken are big ones, it is the little items that are important. For example, there is an old saying, 'Do not cut ferns in any month that has no 'r' in it. This is true, for if you cut them in May, June, July or August they will not bleed, but often grow stronger.

Cut rushes in autumn or early winter, then the young shoots are nipped off by cattle. Cutting in the spring is almost a waste of time, as cattle will eat quantities of roughage only from February to the end of August. On the first week in September cattle will come in from the bush to the grass.

To burn a bush run, remember that to burn one acre (.4 hectares) before Christmas will produce as much winter feed for your stock as ten acres (four hectares) burnt after Christmas. Also the early burning does not hurt the trees, which is very important.

It is very expensive to plant just a few trees and fence them from the stock. We use the log heaps and plant trees in them. The log heaps act as a compost to keep the trees moist and it is not necessary to spend money and time fencing them. Unfortunately the wombats are a problem with the young trees.

However, we have some beautiful trees growing in the log heaps. We have planted all sorts of trees, native trees such as ti-tree, she-oaks, boobyallas, plus pines and even walnuts.

The old English recipe to keep flies away from an area, was to plant walnut trees. We have one near our stock yards, close to our house and this seems very effective.

There is a great opportunity, in my opinion, for planting walnuts commercially in Tasmania. The great market that exists in the Northern Hemisphere probably has its peak price and demand at Christmas time.

It takes many months after harvesting before the walnuts are at their best for selling. It is difficult for those harvested in the Northern Hemisphere in September and October to be at their optimum by Christmas. Therefore there should be a very big opening for us to sell walnuts during this period.

Walnut trees should be able to be mechanically harvested very easily by shaking the trees, and picking up walnuts with a giant vacuum cleaner. Some trees will not stand the shaking and knocking about. Hence the old saying, 'A woman, a dog and a walnut tree, the more you beat them the better they be,' could be right for the former, but I doubt if my lady readers will agree with the whole quotation.

We are just growing them for the aesthetic value and hopefully to help keep the flies away from our sheep.

We have planted numerous trees for shelter and saved natural shelter trees. We picked boobyalla seeds, poured boiling water on them, mixed in pine and flowering gum seed, and sowed them. We have also saved natural scrub in patches, because this is very valuable for the health of the stock.

Eucalypts and Black boys (tree ferns) in foreground.

Cattle and Black Boy dam in background.

Yacca, for example, is poisonous if eaten by itself, but, if eaten together with clover and other pasture, it is a very good source of natural roughage, apart from being very rich in sugars. Bees hang around a broken black-boy, a species of yacca, in swarms for the sugar, and our cattle will not eat molasses, as they get most of their needs from the yacca.

Originally we put trace elements on our soils, mainly copper and cobalt, planning to repeat this only when necessary after testing the livers of our animals for deficiencies. However, because they get plenty of native herbs and shrubs they are extremely healthy. Their coats are shiny and they do not need licks. We have very little trouble with bloat, grass tetany etcetera.

When sowing down a pasture on virgin soil we inoculate our clover seed with the right bacteria and pelletise with lime, and sometimes sow with lime. We do not replough our pastures unless absolutely necessary, because an old pasture is far better in every way than a new pasture. It has a better water-holding capacity, has more digestible protein, and has many more living animals in the soil, which keep it friable and rich.

So we have brought tens of thousands of the right type of pasture worms to this area. Worms burrow to a great depth, and the worm casts, or dung, pass through their bodies and are practically all soluble to the grass and cloven.

It was once thought that shelter trees'main purpose was to shelter old Bess from the wind and rain and stop the wind drying out the property. Now, however, it is realised that this is not the most important function of shelter trees. The billions of live animals in our soil give off gases and the plants breathe these in through their leaves as long as the wind does not blow them away, thereby depriving the pastures of direct food value.

Trees are far more important than most of us realise. They not only have an aesthetic value, for they help to shelter birds and animals and break up the wind force, thereby helping our properties retain moisture and growth. They also supply nests for bees, birds and insects, and all these, together with bountiful soil life, are vital for successful farming operations. We used to spray our pastures to stop army grubs and other pests, but we created a vicious circle by killing the natural predators of these pests. During the last 22 years, however, we have not sprayed and our pastures and our cattle are healthier than ever before, because Nature has now built up a natural balance in regard to soil life.

We have found our soils have been very short of sulphur, so this has been mixed with the superphosphate. With every type of manure we put on, our first question should be whether it helps or hinders our soil life, because this is the vital thing for future economic production of healthy stock and crops.

We have put on more than 25,000 tons of dolomite and lime during the past 26 years. The Smithton dolomite is high in magnesium and to my knowledge, is the best in the State.

Tasmanian and Victorian stock losses add up to hundreds of thousands of dollars with various diseases caused by shortage of magnesium, of which practically all our Tasmanian soils are short, and in the past we have had cattle die through grass tetany and other disorders. Now we have very few.

The first call on magnesium in an animal's or man's body is for the white corpuscles to fight diseases and if they don't get it there they get it from bone marrow. Previously we had to dose our cattle with magnesium, for the vegetation for both animals and humans is short of magnesium, causing our bones to become brittle.

In contrast, in various parts of the U.S.A., where the water supply has plenty of natural magnesium, people who suffer broken hips, even at 80 years of age, mend quickly.

It is now too expensive for us to rail this high magnesium dolomite from Smithton to our property, so we use local supplies, which are reasonable. It is worth noting also that dolomite has one of the highest neutralising effects on acidity of the lime products of Tasmania. Actually, we have areas in the sandhills of our properties where the pH varies from 7.5 to 8.8, so of course this does not need lime of any description, but in other areas the pH can get down to 4.5. The pH, of course, really needs to be increased from 4.5 to enable us to grow successful legumes for pasture establishment.

We grow three main varieties of clover - subterranean, wild white and strawberry. We plant an early and late variety of subterra- nean clover; we use about 1 lb. Trikkala and 1 lb. Karridale. They have a peak growth from September to November. Wild White clover growth is mainly during December and January; strawberry clover flourishes from February to March. The strawberry clover does very well in really wet areas or where the ground is slightly salty.

Some deep-rooted plants are essential in pasture, such as strawberry clover and cocksfoot grass. Extra deeply rooted ones such as lucerne and chicory, also are important. Chicory is used in English organic farming, and what they consider the right weeds are very important in their farming practices.

However, if a variety of plants are grown to extend the natural grazing period, together with some irrigation in the relatively mild climate in our area, it is generally sufficient. In the winter time the stock have additional essential roughage such as lily sags, button grass and other herbs.

In China farmers have 2000 different herbs growing in the high grassland areas which they use for the benefit of the country, but I do not know how many we have and unfortunately our governments have not really been interested in finding out. For instance, the native lilysag, which we do not value enough, is supposed to help prevent scours in calves and definitely helps prevent bloat in cattle.

The commune system in China makes sure the right fertilisers are used to help soil life, thereby also helping fish and other water creatures. It is essential that every section of the commune must benefit by the type of manure used.

My wife and I visited properties in England running two to four cattle per acre, on which no manure of any description, chemical or organic, had been used for 45 years, but grass was topped for mulch for the benefit of worms and soil life. Plants obtain growth from soil life activity, for worms in good old pasture (100 years or more) will produce 24 tons of worm dung or casts per acre.

Sea-weed extract spraying indirectly feeds plants, but more importantly, it is claimed that, by containing all plant food, or at least 51 different known ingredients, it helps the soil life thrive and multiply, thereby directly helping crops and pasture production. We have not used sea-weed extract commercially.

Unfortunately, although our farmers and our governments spend a lot on medicine and drenches, and rightly so, they do not spend sufficient money and research on preventative medicine for man and beast. If this were done on a national basis it would be worth at least hundreds of millions to Australians annually, apart from making it a better, healthier and more congenial place to live.

I hope to work and plan our properties (which are really in trust to me during my lifetime) so they will develop into better, healthier and more beautiful areas.

I know it might seem idealistic to do this and still remain viable in our present world economic situation, but I think it can be done, and I only hope my book, based as it is on practical experience, may have some benefit.

If this is achieved it must benefit every section of our Australian community in some way, and even have some benefit overseas by enabling us to export better-quality foods for world consumption. The world now is demanding better, healthier food.

New office built in 1986, with really good and interesting working conditions.

It overlooks the distant hills and mountains. Our cattle approach the windows

to check on the staff. Helen - office assistant.

Most things in this world are accomplished by using common horse sense, and nowhere is this needed more than in farming. Mr. Yeoman's Keyline farming scheme of diverting run-off water into strategically placed dams, for use in irrigation, is an example of common sense sustainable farming. We are extremely fortunate in Tasmania to have the clean air and water available to help our farming activities produce really healthy food. We should work with Nature, not against it.

I was given a good example of this when I visited the Sacramento Valley, in California, in 1956. Professor Jack Henna was showing me around one day when we were inspecting carrot crops, and he told me they used to depend on the ladybirds to control the aphids in the carrots. But when they started producing large areas of carrots the local ladybird population could not eat sufficient aphids, so the farmers travelled to North Canada and Alaska and brought back great hives of ladybirds which were hibernating like swarms of bees in the forks of trees.

They brought them back in refrigerated trucks, held them near the carrot paddocks and when the local ladybirds could not fully control the aphids, the van doors were opened. The ladybirds came out of hibernation and swooped down on the crops, making short work of the pest.

Of course, a chemical company had to get into the act, saying they could kill the aphids with aerial spraying more quickly. This they did, but they also killed the ladybirds. Later, whether or not so many carrots were grown in this area, they still had to spray, as they had killed the natural predator. This is only one instance of how we can disrupt the environment by working against Nature.

On our property we not only do our own budgeting; we also do our own income tax. We do not use computers in the office, for we have a very simple costing system set up and therefore do not need to change.

It is interesting that in 1988-89 we found more than a thousand dollars worth. of mistakes a week in our accounts, or $54,000 for the year. This, of course, is caused by big firms feeding the wrong information into their computers and then assuming that the information coming out the other end is correct and needs no rechecking.

This isa very sloppy way to do things, and proves that everyone must be right on the ball to do things properly. I realise that computers are wonderful and the modem world could not manage without them, but it is no good, as some farmers do, sitting in front of a computer and getting a pile of figures in front of them and assuming that everything they see is correct.

One has to be practical and down to earth and keep one's feet firmly on the ground. Costs must be checked and it is only practical to realise that a computer is only as accurate as the information that is fed into it. You can bamboozle yourself with figures; yet I know that many people depend on the machine entirely.

I recently bought 142 head of cattle at a sale in Tasmania. I called on a livestock company with the agent and, while he was talking to his boss in the office I asked a lass to tell me how much these cattle averaged. She was a nice girl, and very co-operative, and she went flat out trying to work the figures out, and came up with a figure of $331. I said that was just impossible, as, according to the list of the cattle I had bought they would not average more than $260. The young lady was adamant. She checked with a man in the office, and came back to say that the figure she had quoted was exactly right.

I tried to show her that it was clear from the list that the average could not be $331, because the highest price was only about $335. But she was used to looking at the machine and could not work out anything herself, so I told her to forget about it and I would check it at home, but she did it again and got it exactly right, at $253.87. But until I insisted that she was wrong her figure was right in her opinion, for she had lost the knack of creative thinking.

I had a score of students looking around our property once. They did not have their calculators with them and they could not work out anything without them - they had lost the art of creative thinking. This proves that, although it is useful to have calculators, we must not become machine-minded.

We have never had to pay any additional sums to the Taxation Commission nor will we ever have to do so, as we discuss any problem with them before the taxation is lodged. This is quite an advantage if you know your finances. You must know how you are going - whether you are spending too much a year or, on the other hand, whether you have quite a lot of money available at the end of the year.

If the latter is the case you may consider planting another 10,000 trees, putting on another 500 tonnes of dolomite or distributing extra worms and dung beetles in the last two months of the financial year.

In short, you must know how you are going and what you are doing day by day if you are to stay in front. So many good businessmen haven't a clue about their own finances; they depend entirely on outside people, and this is not always efficient.

In the development of the Wyambi properties the development techniques, budgeting, costing, records and managerial practices were all personally worked out by me and my staff, and were carried out with the minimum of outside help.

In my book the costing systems and programmes are very simply illustrated so any grazier or farmer can read and understand all parts of this book and hopefully follow any parts of it which would beneficially suit his enterprise.

Hopefully the readers will not only be inspired to make their properties more attractive areas for themselves and their families, but also more viable enterprises. The ordinary citizen driving through the countryside will feel enlightened and refreshed because properties look so lovely and yet productive, as they can be when the farmers work with Nature and not against it.